In November 1918, France was physically and mentally scarred. World War One was ending, yet the victory had come at an enormous cost. Of the 8 million Frenchmen mobilized, more than a million had died and another million were crippled. Eastern France had been almost continuously occupied by enemy forces for four years. Consequently, the country’s most advanced agricultural and industrial areas were devastated.

A big question emerged after the war: how could France best defend itself against future attack? The question took on greater urgency after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. The treaty punished and crippled the war’s aggressor, Germany, yet France believed that the Germans had gotten off lightly and war would resume soon enough.

There was one problem: Germany didn’t end up attacking France via the Maginot Line. In 1940, it attacked the Netherlands, then moved through Belgium, to enter France. Germany met little resistance and France was subjected to a quick and embarrassing conquest.

After World War Two, the Maginot Line came under severe criticism both in France and abroad. In hindsight, it’s easy to pick flaws with the idea. At the time though, France thought it was learning from the recent past and applying that knowledge to the future.

There was one problem: Germany didn’t end up attacking France via the Maginot Line. In 1940, it attacked the Netherlands, then moved through Belgium, to enter France. Germany met little resistance and France was subjected to a quick and embarrassing conquest.

After World War Two, the Maginot Line came under severe criticism both in France and abroad. In hindsight, it’s easy to pick flaws with the idea. At the time though, France thought it was learning from the recent past and applying that knowledge to the future.

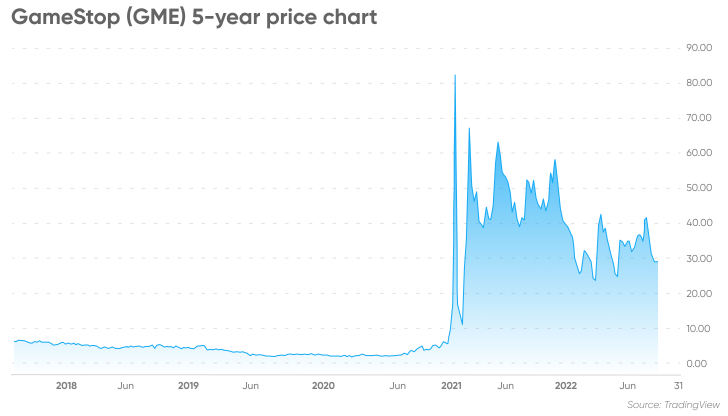

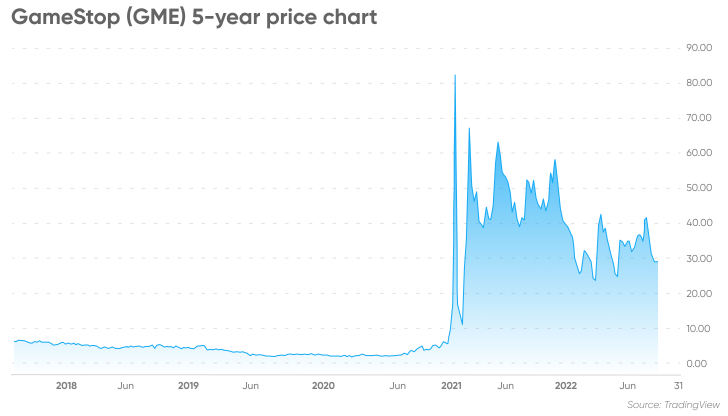

To avoid the fate of France and indeed Bitcoin and GameStop speculators, it’s worth looking at recent events which investors may need to be careful extrapolating or overweighting into the future. They include:

To avoid the fate of France and indeed Bitcoin and GameStop speculators, it’s worth looking at recent events which investors may need to be careful extrapolating or overweighting into the future. They include:

A safe France

After a decade-long debate, a key pillar of French defence against future attack was decided. It became known as The Maginot Line. The idea came from fortifications around Verdun which had worked well during World War One. They had held up to extensive artillery fire and suffered minimal damage. The Maginot Line would be an extended series of large-scale buildings along the south-eastern French border. It would defend the region most vulnerable to attack. With the south-east fortified, France could focus on gathering forces in the north-east of the country, to get ready to enter, and fight in, neighbouring Belgium. Belgium was a key ally of France in 1930, when the building of the Maginot Line commenced.Not as safe as assumed

France largely completed construction of the Maginot Line (pictured below) by 1936 and the country felt safe. After all, what worked in World War One had been extended and would shield the country from future attacks. There was one problem: Germany didn’t end up attacking France via the Maginot Line. In 1940, it attacked the Netherlands, then moved through Belgium, to enter France. Germany met little resistance and France was subjected to a quick and embarrassing conquest.

After World War Two, the Maginot Line came under severe criticism both in France and abroad. In hindsight, it’s easy to pick flaws with the idea. At the time though, France thought it was learning from the recent past and applying that knowledge to the future.

There was one problem: Germany didn’t end up attacking France via the Maginot Line. In 1940, it attacked the Netherlands, then moved through Belgium, to enter France. Germany met little resistance and France was subjected to a quick and embarrassing conquest.

After World War Two, the Maginot Line came under severe criticism both in France and abroad. In hindsight, it’s easy to pick flaws with the idea. At the time though, France thought it was learning from the recent past and applying that knowledge to the future.

Recency bias

Investors often make the same mistake that undid France. Behavioural economists call it recency or extrapolation bias. It’s a cognitive bias, or mental mistake, where investors incorrectly believe that recent events will happen again soon. Put another way, investors often overweight new events or information without looking into the objective probabilities of those events occurring in the long run. Think of last year’s bubble price action in the likes of Bitcoin and GameStop, and how investors (or more aptly, speculators) thought the huge increases in prices for these things would continue without looking objectively at the long-term fundamentals. To avoid the fate of France and indeed Bitcoin and GameStop speculators, it’s worth looking at recent events which investors may need to be careful extrapolating or overweighting into the future. They include:

To avoid the fate of France and indeed Bitcoin and GameStop speculators, it’s worth looking at recent events which investors may need to be careful extrapolating or overweighting into the future. They include:

- Rising interest rates though everyone expects them to remain relatively low.

- A pullback in bond prices making them attractive versus recent history.

- The traditional 60:40 equities/bond portfolio failing miserably this year, with calls for it to be adjusted or discarded.

- The US$ becoming ‘king dollar’ and the pound, Euro and Yen getting pulverised.

- Growth stocks coming back and being set for further outperformance given their superior performance since 2008.

- Most Australian superannuation funds having outperformed their benchmarks, with expectations of more to come.

- Venture capital and private equity continuing their ascent in the finance industry.

- Significant government debt having not been an issue (until very recently).

- Gold being one of the few assets to have performed well in A$ terms this year, with predictions of further outperformance going forward.

- Volatility being back. Period.